Biography of Hoagy Carmichael

By John Edward Hasse

The year 1899 was a seminal one in American music. In the space of seven months, three auspicious events took place. Scott Joplin published his Maple Leaf Rag—whose acceptance would become emblematic of the mainstreaming of African-American music in American culture. And two figures were born who would play pivotal roles in 20th century music—Duke Ellington and Hoagy Carmichael.

While you read, why not listen to a record of Mr. Carmichael singing and playing Stardust?

You'll even get to hear the surface noise of… is it vinyl or shellac? Both were around.

Born Hoagland Howard Carmichael in Bloomington, Indiana, he grew up in modest circumstances. His father earned an on-again, off-again living as an electrician. His mother played piano for dances at local fraternity parties and at “silent” movies. Hoagy would tag along. Like a sponge, he absorbed music from his mother, from visiting circuses, and from the black families and churches in his neighborhood. Ragtime was in the air, and his mother mastered the Maple Leaf Rag and other popular tunes of the day.

In 1916, his family moved to Indianapolis. There, Hoagland came under the influence of an African-American pianist named Reginald DuValle, who gave him a great piece of advice: “Never play anything that ain’t right,” he admonished the young pianist. “You may not make a lot of money, but you’ll never get hostile with yourself.” DuValle gave Carmichael pointers about playing hot ragtime and the emerging style of jazz. Carmichael sought out cheap pianos in restaurants, night spots, and brothels where he was allowed to sit in.

With Harold Russell in 1946 during production of “The Best Years of Our Lives.”

Back in Bloomington in 1919, Carmichael booked the Louisville-based band of Louie Jordan (not the later jump-blues singer), and this experience spurred Carmichael into becoming a self-described “jazz maniac.” He also listened to records avidly. He made a trip to Chicago, where he heard Louis Armstrong—a musician who would influence him (and with whom he would record later).

After completing high school, Carmichael entered Indiana University where, judging from his memoir The Stardust Road, it would seem he majored in girls, campus capers, and hot music. He reveled in a growing passion for jazz, and started his own group, “Carmichael’s Collegians,” which developed a reputation not only on campus, but in the region, as they traveled through Indiana and Ohio to entertain young dancers.

In the spring of 1924, Bix Beiderbecke—a young cornetist out of Davenport, Iowa—came to Indiana University. Carmichael booked him to play a series of ten fraternity dances, and the two became fast friends. It was for Beiderbecke that Carmichael wrote his first piece, titling it Free Wheeling. Beiderbecke took it with him to Richmond, Indiana (100 miles to the East), home of the early record company, Gennett Records, and waxed it with his seven-piece band, “The Wolverines.” It was now retitled Riverboat Shuffle.

From “Night Song” with Dana Andrews and Merle Oberon, 1948.

Carmichael himself got a chance to record at Gennett studios in 1927. One of the numbers he recorded on Halloween, 1927, was an up-tempo wordless original called Star Dust. Initially it landed with a thud.

Meanwhile, Carmichael managed to secure his Bachelor’s degree in 1925 and a law degree in 1926, both at Indiana University. After completing his law degree he briefly hung out a shingle in West Palm Beach, Florida, but after happening on a recording of his song Washboard Blues, he gave up law for good in favor of music.

Carmichael closed the chapter on the first of three periods in his life when he left Indiana in 1929 and moved to New York City—where you had to go to make it in the music business. By day he worked for a brokerage house, while by night he wrote songs and made musical contacts—among them his idols Beiderbecke and Louis Armstrong, as well as the Dorsey brothers, clarinetist Benny Goodman, trombonist Jack Teagarden, and a hopeful lyricist out of Savannah, Georgia, named Johnny Mercer—ten years Carmichael’s junior. They began writing songs together, such as Lazy Bones, which became a huge hit in 1933, even at the depth of the Depression.

In January, 1929, Mills Music Company of New York published Carmichael’s Stardust, still a wordless instrumental. In May of that year, the piece was published as a song, with lyrics by Mitchell Parrish, a New York lyricist working for Mills. But still the song went nowhere. In May, 1930, bandleader Isham Jones recorded the song, slowing the tempo. Now the song began its skyward ascent, as more and more musicians were attracted to its dreamy, romantic qualities.

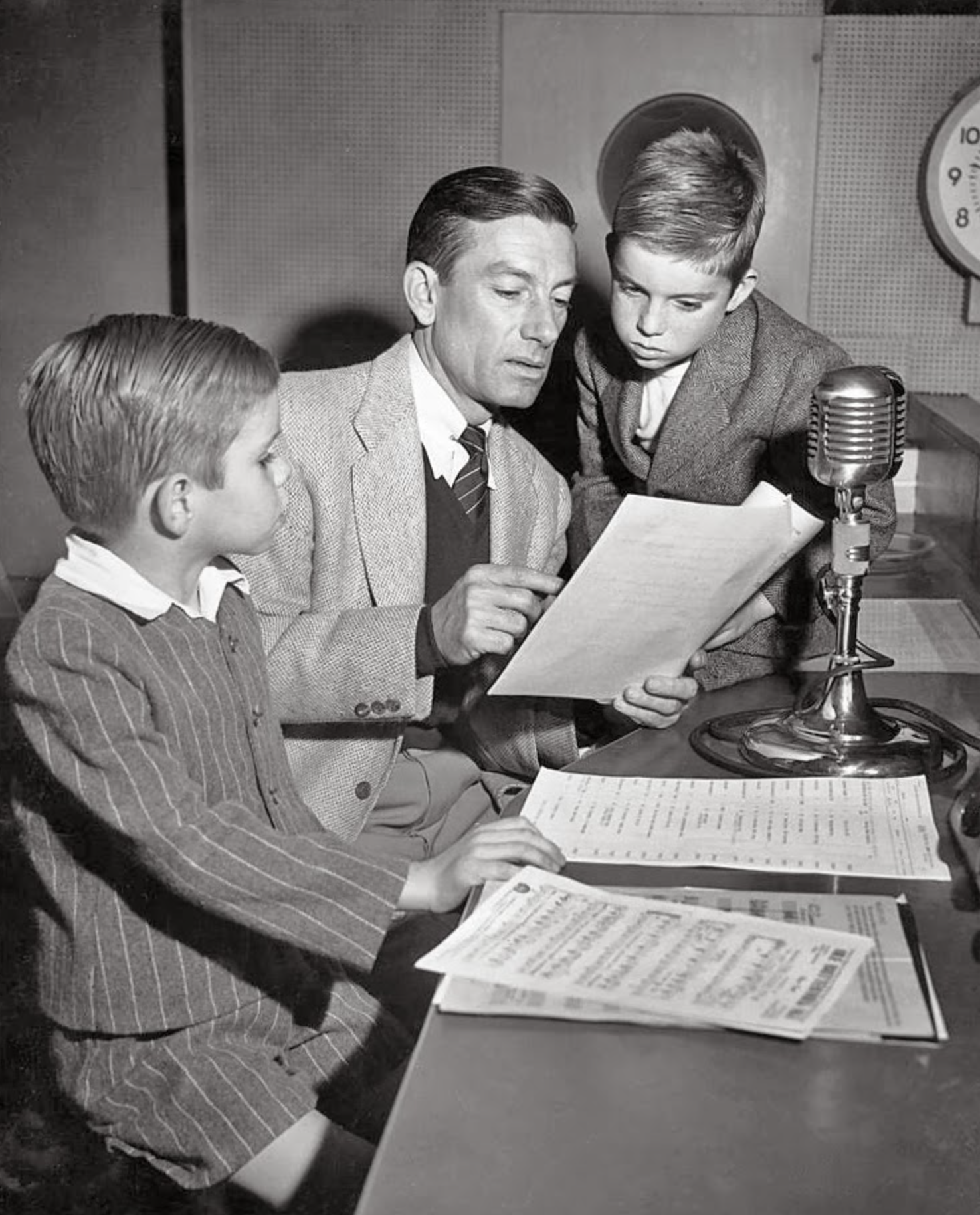

Carmichael duriing his radio show with sons Randy Bob and Hoagy Bix.

Carmichael was now writing folksy songs that would become jazz standards—notably Rockin’ Chair (copyrighted in 1930) and Lazy River (1931). During the five years from 1929 to 1934, Carmichael made 36 recordings for the Victor company—the nation’s leading record label. He was rubbing elbows—and recording—with some of the great talents in jazz: Louis Armstrong, Henry “Red” Allen, Bix Beiderbecke, Benny Goodman, Mildred Bailey, and Jack Teagarden. In 1931, he was admitted to membership in the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP), signifying his arrival in the songwriting fraternity.

In 1931, the death of his close friend Beiderbecke closed a chapter in his life and seemed to lessen his fire for jazz. By the mid-1930s, he was enjoying considerable financial success as a songwriter, and the mainstream beckoned him.

He made several life changes in 1936. He married Ruth Meinardi of Winona Lake, Indiana. The couple would have two sons—Hoagy Bix and Randy—though the marriage would break up in 1955. And in 1936 Carmichael left New York City for good, thus closing the second big chapter in his life.

He moved to Hollywood, where, as he put it, “the rainbow hits the ground for composers.” Thus began the third and final phase of his musical career. Working for Paramount Pictures, he teamed with lyricist Frank Lœsser on such songs as Two Sleepy People, Small Fry, and Heart and Soul. In 1939, Carmichael and Mercer collaborated on a Broadway musical, Walk with Music, but it closed quickly; this would be Carmichael’s only foray into musical theater. Otherwise, he composed “independent songs”—songs meant to stand alone from any production—as well as songs for the motion picture industry.

After a bit part as a piano player in the 1937 film “Topper,” Carmichael was given roles in other movies, including “To Have and Have Not” (1942) where Lauren Bacall introduced How Little We Know. Then followed “The Best Years of Our Lives” (1946), “Canyon Passage” (1945, where his performance of Ole Buttermilk Sky helped make it a hit), and “Young Man with a Horn” (1950), a fictionalized life of his good friend Beiderbecke.

In the 1940s, Carmichael’s career took off in multiple ways—as a songwriter, as a singer (recording for three labels), as a movie actor, and as a radio star (he had his own series on three networks), and as an author (his first book of memoirs, The Stardust Road, was published in 1946). More than any other decade, the 40s marked the peak of his career and popularity.

One of his songs from 1942, the resplendent Skylark (with a fine Mercer lyric), like Stardust, seemed to have the improvisations built right into the melody; it became a standard among singers and jazz musicians. In many of his songs from his California years, however, the jazz influence is not obvious.

Another collaboration with Mercer, the 1951 film song In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening earned Carmichael an Academy Award for best song. Several of his 1950s songs—My Resistance Is Low and Winter Moon—found modest success, and he continued to compose, but he would have no more major successes as a songwriter. He had enjoyed a fertile creative run of more than twenty years—no mean feat in the fast-evolving, fickle world of popular music. And popular tastes in music were changing in the 1950s-rhythm and blues. Rock and roll brought harmonically simplified songs heavy with beat to the fore, grabbed young listeners, and began taking over the airwaves. The “golden era” of American popular song, in the view of many, was over.

But once launched, many of Carmichael’s songs took on lives of their own, finding favor and permanent homes in the repertories of singers and instrumentalists from various corners of American music. When, for example, Ray Charles made a huge hit and earned a Grammy Award for his moving rendition of Georgia, it helped the song find new audiences and live on in cultural memory. Already an evergreen, Stardust grew taller and stouter during the late 1950s and the 1960s, and RCA Victor even issued an LP, The Stardust Road, with nothing but different versions of the song. In 1965, his second book of memoirs, “Sometimes I Wonder,” was issued.

Autographing record albums for eager fans.

Carmichael became something of a fixture on television in the 1950s, even playing a straight dramatic role on the TV Western, Laramie, in 1959-60. He became an avid golfer and coin collector, and still wrote songs—though hardly any of them were to be recorded. He maintained an interest in children and in 1971 published Hoagy Carmichael’s Music Shop, a collection of songs he composed for children.

In 1977, Carmichael married the actress Wanda McKay after what was termed “a long courtship.” Golf and coin collecting were two avid pursuits. He returned a number of times to his native Indiana, and, as his years grew, was increasingly honored. In 1972, Indiana University awarded him an honorary doctorate and in 1974, the university’s rare book archive, the Lilly Library, curated an exhibition in his honor. In 1979, Carnegie Hall held a tribute concert. In 1980, a stage production, Hoagy, Bix, and Wolfgang Beethoven Bunkhaus moved from England to the United States, playing in Indianapolis and Los Angeles.

After suffering a heart attack, Carmichael died at his home in Rancho Mirage, California, on December 27, 1981. His body was returned to his native Bloomington for burial.

In the years after his death, his place in the cultural firmament has slowly risen. His family donated his archives and memorabilia to Indiana University, which in 1986 opened the Hoagy Carmichael Room in his honor. In 1988, the Indiana Historical Society and the Smithsonian Institution issued a lavishly illustrated boxed set of recordings, The Classic Hoagy Carmichael, which earned Grammy Award nominations for Best Album Notes and Best Historical Album. In 1997, the United States Postal Service, acting on a recommendation from this author, issued a commemorative postage stamp in his honor. During his centennial year of 1999, there were radio broadcasts, concert programs, and songbook publications. His two memoirs were restored to print when Da Capo Press issued them in a combined edition—The Stardust Road and Sometimes I Wonder: The Autobiographies of Hoagy Carmichael. Then came word of a forthcoming biography by the cornetist and author Richard M. Sudhalter.

A scene from 1944’s “To Have and Have Not,” with Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart.

With rare exceptions, until Carmichael came along, songwriters were a separate group from singers. Something of a modern minstrel, Carmichael was one of the first singer-songwriters in the age of mass media. He paved the way for later such performing writers as Bob Dylan, Billy Joel, Bruce Springsteen, and Joni Mitchell. His down-home Hoosier accent and singing style he described as “flatsy through the nose” made him seem like one of the people. In fact, more so than many songwriters (for example, fellow Hoosier Cole Porter), Carmichael’s songs appealed to all sections of American society—from the Wall Street broker to the sharecropper farmer. He was a musical democrat.

If Carmichael’s singing voice was as unmistakable as his nickname “Hoagy,” similarly no one would mistake his songs for those of Gershwin or Porter or any other songwriter. While there is no single Carmichael “sound,” his songs nonetheless sound like him. His melodies are so strong and distinctive that they usually dominate the other elements of his songs. Many of these melodies move to unusual intervals, cover a wide range, and display the instrumental influence of jazz. Most have few repeated notes, and most travel an unpredictable path—they are fresh. And that’s one reason why so many of them have remained with us for decades.

His two greatest songs—Stardust and Skylark—reveal deep jazz influences: eloquent, lyrical, striking melodies that seem like Beiderbeckian solos captured for all time. The composer himself said, “The Bix influence was there. And the improvisations are already written.” Other songs reveal a gift for harmony: the unusual chord progressions in Baltimore Oriole, the unconventional harmonies that end Rockin’ Chair, and creative middle sections (what musicians call “the bridge”) of both Skylark and Georgia, and the abrupt key change in the chorus of Washboard Blues. His music was deeply rooted in his native Indiana, and in the ragtime and jazz he grew up with, as much as any influence from Tin Pan Alley. He turned instinctively to the vernacular sounds of Indiana, New Orleans, and Chicago. His world of songs was often small-town, early twentieth-century America, a time of Lazy Rivers, old Rockin’ Chairs, and Watermelon Weather.

So familiar and timeless were Carmichael’s songs that several entered aural tradition. Rockin’ Chair seemed to some so down-home that they thought it a folk song. With its repeating notes and stepwise melodic motion, Heart and Soul was so easy to remember that, in the years after 1950, it became familiar to virtually every American kid with a piano and a pal to play the other part. It was common coin among children.

And so it was—through the uniqueness of his songs, the charm of his performances, and the technology of the mass media—that Hoagy Carmichael’s music found a place in the American consciousness, and that of much of the English-speaking world. His songs are at least as enduring as many public buildings of his day. And no doubt they will continue to give meaning and pleasure to people for a very long time.

Copyright Information—Indiana University provides the information contained on this web page, including reproductions of items from its collections, for non-commercial, personal, or research use only. Photo of Mr. and Mrs. Carmichael courtesy of Indiana University.